The Anatomy of the Analogy: When Weak is Not Weak and False is Not False

February 18, 2020Categories: Logically Fallacious,

The Dr. Bo Show with Bo Bennett, PhD

The Dr. Bo Show is a critical thinking-, reason-, and science-based approach to issues that matter. It is the podcast of social psychologist Bo Bennett. This podcast is a collection of topics related to all of his books. The podcast episodes, depending on the episode, are hosted by either Dr. Bennett or Jerry Sage, discussing the work of Dr. Bennett.

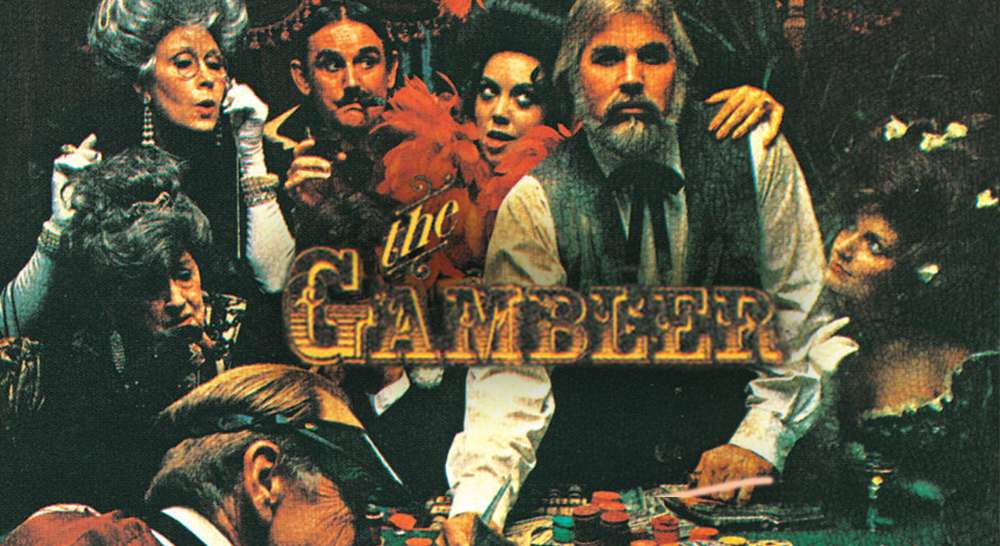

The analogy is one of the most useful tools in argumentation as well as one of the most helpful aids in effective reasoning. It allows us to compare something with which we are familiar to something with which we are unfamiliar, then use the similarities to check for consistency in our reasoning. But thanks to our stubbornness, our refusal to be wrong, and our allegiance to ideology over reason, we flippantly dismiss analogies that don't support our position by labeling them "weak analogies" or "false equivalence," robbing ourselves of the opportunity to grow intellectually. As the great Kenny Rogers once said, and I am paraphrasing, you got to know when accept 'em, know when to reject 'em, know when to call "fallacy," and know when to learn.

Let's begin with the fact that all analogies are different in some way from that to which it is being compared. If they weren't, it wouldn't be an analogy. However, a strong analogy might say how two similar things are equivalent in some specific way. Here is where committing the false equivalence fallacy becomes a possibility. This is an argument or claim in which two completely opposing arguments appear to be logically equivalent when in fact they are not. The confusion is often due to one shared characteristic between two or more items of comparison in the argument that is way off in the order of magnitude, oversimplified, or just that important additional factors have been ignored. The false equivalence fallacy requires a claim of equivalence, usually identified by the phrases "no different than," "same as," or similar language establishing "sameness." Consider the following example,

President Petutti ordered a military strike that killed many civilians. He is no different than any other mass murder, and he belongs in prison!

While it is the case that both president Petutti and mass murderers share the characteristic "responsible for the deaths of many civilians," the (implied) claim is that they share the same legal culpability, which is not the case.

Next, analogies that are ambiguous are not good analogies. Very often, one will make an analogy and not be clear as to why what is being compared is similar. If I said apples are like oranges, and just left it there, confusion would ensue. In some ways, apples are like oranges, and in some ways, they are not. By simply adding why they are alike, we can solve this ambiguity problem. "Apples are like oranges in that they are both fruits." One can be deliberately ambiguous to avoid having to justify their analogy and just make a statement that has a powerful emotional impact. For example,

A vote for Trump is like a vote to end democracy as we know it!

Okay, but why is a vote for Trump like a vote to end democracy? By not providing a reason how the two are similar, we leave it up to the imaginations of the audience. This is wholly unhelpful because pro-Trump folks would simply disagree. This is like just stating a conclusion without providing any premises. If your goal is to get support from those who already agree with you, fine, but if your goal is to convince people who don't agree with you, you must remove the ambiguity and connect the dots for the audience by telling them how the two are alike. You might list the ways in which Trump has interfered with democracy, then compare how this is a significant change from how democracy has changed under other presidents. If you fail to make your case, you may be called out on a weak analogy.

Analogies that are weak are not good analogies and considered fallacious. When an analogy is used to prove or disprove an argument, but the analogy is too dissimilar to be effective, that is, it is unlike the argument more than it is like the argument, then we call this a weak analogy (or weak analogy fallacy). Ambiguous analogies are often weak because the entirety of two things are being compared rather than a specific characteristic shared by the two things. The vote-for-Trump analogy could be reasonably argued to fall somewhere on the weak to strong continuum. If you want to virtually ensure you are making a strong analogy (and not a fallaciously weak one), be specific and clear in your analogy by answering how or in what way the two things being compared are similar. For example,

If we should implement stop and frisk because it "saves lives," then by the same reasoning, we should ban cars because that would undoubtedly save lives.

Here we are comparing implementing two policies: stop and frisk and banning cars. We are saying they are similar in that they both save lives. It is in that regard, and only in that regard that the comparison is being made. Clearly, there is a sense of irony in this argument. The person is not seriously suggesting that we should ban cars, but the implication is that just "saving lives" is not a sufficient reason to implement a policy. This is effectively an argumentum ad absurdum (i.e., suggesting that implementing a policy just because it "saves lives" leads to absurd conclusions when we apply this to other possible policies).

Bring on Kenny

You gotta know when to accept 'em. If the analogy is specific in how the two things are similar, and it is true that they are both similar in that regard, you should accept the analogy with its limitation (i.e., the claim is that the two things are analogous in regards to the specific shared feature only).

You gotta know when to reject 'em. If the analogy fails to be specific and fails to clearly state or even clearly imply how the two things being compared are similar, and there are more differences between the two than similarities (or the similarities differ significantly in degree), then you reject the analogy as a weak analogy. For example, "Believing in God is like believing in Santa Claus," can generally be regarded as a weak analogy. One can make a list of hundreds of properties of God and Santa, and the differences (in number and degree) would clearly exceed the similarities. In order to strengthen such an analogy, we might say something such as "God is like Santa Claus in that both God and Santa are represented as old white guys with long grey hair and beards who are said to see you when you're sleeping, know when your awake, and know when you've been bad or good."

You gotta know when to call "fallacy." We have already seen the weak analogy, let's now look at the extended analogy fallacy which is suggesting that because two things are alike in some way and one of those things is like something else, then both things must be like that "something else." For example,

Hitler had a mustache. Your dad has a mustache. Therefore, your dad is a psychopathic dictator.

While it is true that Hitler is like the person's dad in that they both have mustaches, concluding from that the dad must also be a psychopathic dictator is fallacious.

You gotta know when to learn. You should treat every analogy presented to you as a learning experience. Ask questions such as

- How are these two things the same?

- How are these two things different?

- In the ways they are the same, are they the same but in significantly different ways (e.g., President Petutti may be responsible for the deaths of many innocent civilians just like a psychotic mass murderer, but the reasons behind the deaths are significantly different enough to make the claim of equivalence fallacious).

- Is the claim of similarity specified, or is it left ambiguous (therefore, generic)?

- Does the analogy work as a legitimate reductio ad absurdum that points out a flaw in your reasoning?

Analogies are extremely useful tools that every critical thinker should have at their disposal. They can be quite persuasive, but they can also be quite deceptive. Use them, don't abuse them, and learn to spot when others are abusing them by considering analogies carefully before dismissing them as fallacious or simply accepting them because they are ideologically pleasing to you.